A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. A young immigrant mother commutes across Paris for work. Tags: class, economic sociology, emotion/desire, gender, globalization, immigration/citizenship, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, care deficit, motherhood, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006 Length: 4:50 Access: YouTube Summary: The anthology film Paris, je t'aime (2006) features 18 short films set in different neighborhoods—or, "arrondissements"—across Paris. The fifth segment, entitled Loin du 16e (which translates into "Far from the 16th"), takes place in the 16th arrondissement; it was written and directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomas, and stars Catalina Sandino Moreno. The film tells the story of a young immigrant mother who leaves her baby in daycare so she can travel far across town to care for the baby of her wealthy employer; she sings the same Spanish lullaby ("Qué Linda Manita") to stop both babies from crying. Despite being short in length and dialogue, the film offers multiple avenues of inquiry for teaching about many core sociological concepts, including gender, motherhood, immigration, class, globalization, and transnational labor markets. In their edited anthology Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Hochschild highlight the various dimensions—both positive and negative—of immigrant women's entry into "First World" labor markets, which include immigrant women's ability to send money back to home countries, First World women's ability to pursue upwardly mobile paid careers, and emotional hardships and physical strains associated with leaving family and loved ones behind. Ehrenreich and Hochschild argue that this transnational economic process results in a care deficit, in which transnational women's labor supplies much needed care in rich countries, at the expense of creating a deficit of care in home countries. Instructors can focus on the following features of the film to facilitate discussion and analysis: (1) The significance of distance and space. What are the different environments the woman must travel through for her commute to work? Have students read about the 16th arrondissement and then ask: What is the meaning of the film's title, "Far from the 16th"? (2) The significance of power relations. What do we know about the relationship between the woman and her employer (whose face we never see)? What is the significance of the employer's request that the woman work late? Should the woman receive overtime pay for this extra work? Do you think she'll receive it? Why or why not? (3) The significance of the lullaby. Although she sings the same lullaby with the same purpose (to calm a crying baby), how do the two scenes differ? Focus on the environment in which the lullaby is sung, the recipient of the lullaby, the woman's relationship to each of these recipients, and how these factors shape the emotions attached to the lullaby. To view Loin du 16e in French, click here; to view it with Spanish subtitles, click here. For another clip that examines social inequality by interrogating ideas about distance, space, and lullaby, click here. Submitted By: Valerie Chepp

1 Comment

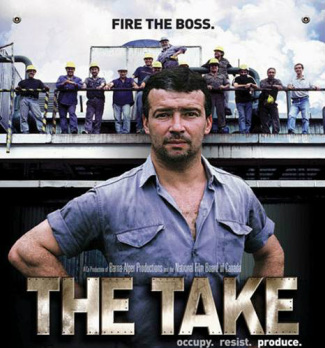

The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. The Take documents factory takeovers in Argentina. Tags: capitalism, class, economic sociology, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, social movements/social change/resistance, theory, factory takeovers, labor, occupy, real utopias, worker cooperatives, subtitles/CC, 61+ mins Year: 2004 Length: 87:00 Access: YouTube Summary: This excellent documentary from Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis documents the extraordinary movement of factory takeovers in Argentina. As noted on the The Take's website, "In the wake of Argentina's dramatic economic collapse in 2001, Latin America's most prosperous middle class finds itself in a ghost town of abandoned factories and mass unemployment. The Forja auto plant lies dormant until its former employees take action. They're part of a daring new movement of workers who are occupying bankrupt businesses and creating jobs in the ruins of the failed system." By following the struggle of the Forja workers to regain control over its factory, it shows how workers formed networks and coalitions in their movement, the legal context of recuperated factories, the different organizational structures that workers develop to run their factories, the political reaction to neoliberalism, and the electoral race to shape Argentina's future. Accordingly, the movement serves as a unique bottom-up alternative to neoliberal capitalism. The film offers excellent illustrations of several sociological concepts, such as class consciousness and ideology. It also reflects Erik Olin Wright's concept of real utopias, which are "utopian ideals that are grounded in the real potentials of humanity ... [including] utopian designs of institution that can inform our practical tasks of navigating a world of imperfect conditions for social change" (2010: 6). As a "real utopia," the recuperated factories represent actually existing social projects that embody ideals of social justice, equality, and participatory democracy--they are not perfect (no social projects are), but they can serve as one model (of many) for what is possible. While the documentary was released in 2004, viewers may be interested to know that the movement of recovered factories continues in Argentina, including hundreds of workplaces and over 10,000 workers. For books on the movement of worker-run factories in Argentina, see Sin Patrón (2007) and The Silent Change (2009). There is also a recent (2013) example of one such factory in the US, Chicago's New Era Windows Cooperative. Submitted By: Paul Dean  This child has a rare disorder and is nearly blind from Agent Orange. This child has a rare disorder and is nearly blind from Agent Orange. Tags: environment, globalization, health/medicine, war/military, agent orange, chemical warfare, dupont, vietnam war, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 4:09 Access: New York Times Summary: This New York Times video examines the relationship between chemical war and the long-term effects on human health. As The New York Times reported in the accompanying article, "Over a decade of war, the United States sprayed about 20 million gallons of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, halting only after scientists commissioned by the Agriculture Department issued a report expressing concerns that dioxin showed 'a significant potential to increase birth defects.' By the time the spraying stopped, Agent Orange and other herbicides had destroyed 2 million hectares, or 5.5 million acres, of forest and cropland, an area roughly the size of New Jersey." Forty years later, there are areas where no plant life will grow and the human health toll is becoming more clear. One example of this is the child in the image here, who has a rare bone marrow disorder that has made him nearly blind and has required he has a blood transfusion every 2 weeks. As a result of long-term effects like this, many Vietnamese people continue to hold bitterness toward the US government and argue that the US has not taken responsibility for its activities, which many people believe were criminal. In 2012, the US government launched its first program to clean up some of the Agent Orange (which includes $43 million in funding to clean up one site where the soil remains highly contaminated and provide a program to help disabled victims). One American advocate of providing this assistance says that the key to securing US cooperation is to focus on assisting the disabled and not focus on who was responsible; he argues "after so many years, why waste time arguing about the past? why get involved in the blame game?... Let's help everyone in need." Some critics say this does not go far enough and some parents of the victims want financial compensation. Viewers may consider whether the US has responsibility for the long-term effects of Agent Orange in Vietnam? What responsibilities does this include and are they going far enough? For example, does the US owe financial reparations to victims? Does Dow Chemical (the manufacturer of Agent Orange) have any responsibility? Submitted By: Paul Dean  "Poor Us" examines the changing world of poverty. "Poor Us" examines the changing world of poverty. Tags: capitalism, class, globalization, historical sociology, inequality, methodology/statistics, political/economy, absolute poverty, antônio conselheiro, charity, colonialism, comparative historical analysis, industrial revolution, poorhouse, relative poverty, social history, welfare state, workhouse, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 58:05 Access: YouTube Summary: This exquisitely animated documentary tells a sweeping social history of world poverty. You, the viewer, are the protagonist in this film floating through the meandering jet stream of world history. "If we want to make poverty history," the narrator explains, "then first, we need to understand the history of poverty." ● The documentary appropriately begins in prehistory (2:35), and in a more or less linear fashion, moves through humanity's early large scale civilizations, including ancient Egypt (4:40) and ancient Greece (5:40). Zipping forward to the Middle Ages, the story unfolds again in Cairo (8:20), and then lingers in Paris of the same period (10:50). The history of colonialism is woven into the story with a look at the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire (14:20), the Portuguese conquest of West Africa (16:20 and 34:40), and British colonial rule in India (36:00). Poverty in a neocolonial context is later examined in Ghana (38:50 and 43:55), and China makes appearances as the site of both model relief efforts and tragic famine (18:30 and 43:20). At the 20:30 mark the story returns to Western Europe in order to consider the impact of the Industrial Revolution on poverty, and then moves toward a conclusion which contemplates the changes wrought by globalization. ● While this 58-minute film understandably fails to deliver a truly exhaustive account of the the world-historical processes associated with poverty, the film would be an excellent tool for illustrating comparative historical analysis in sociology. Systematic comparison is of course central to comparative historical work, and this film succeeds in illustrating the importance of comparison by briefly drawing on eighteenth century China as a rare instance where prosperity for some didn't necessarily come at the cost of desperate poverty for others. What does the film's analysis of poverty gain by including this "negative" case in the story? One answer is that the case of China complicates the viewer's understanding of poverty by exposing its causes as far less determined and far more contingent. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Scene from LA Times video, "The Challenge Ahead" Scene from LA Times video, "The Challenge Ahead"

Tags: abortion/reproduction, consumption/consumerism, demography/population, environment, food/agriculture, globalization, inequality, rural/urban, 06 to 10 mins

Year: 2012 Length: 5:12 Access: Los Angeles Times Summary: This short video, "The Challenge Ahead: Rising Numbers, Shrinking Resources," accompanies a five-part series from the Los Angeles Times and highlights the causes and consequences of the global population explosion. Demographers anticipate continued population growth driven by the reality that there are now 3 billion people on the planet under the age of 25, and about 1.2 billion of them are adolescents who are entering their reproductive years. Projections suggest that by 2050 there will be well over 9 billion people on the earth, and the video highlights many of the resource demands of this many people. For instance, Jonathon Foley of the Institute on the Environment asks, "how are we going to feed 9 billion people without trashing the planet?" and Joel E. Cohen notes that humans are currently consuming resources on planet earth as if the earth were about 50% more productive. The connection between consumption (and production) and population is also explored in Foley's 2011 Ted Talk, where he reports that the total area humans are currently using for agriculture is about the size of South America (16 million square kilometers), while the total area used as pasture and range land is about the size of Africa (30 million square kilometers). Humans are also currently using about 50% of Earth's fresh water, and of this share, about 70% is used for agriculture. But after connecting population growth to agricultural demands, it is only a short distance to discussions exploring the connections between population and environmental degradation, or even climate change. After all, as Foley also points out in his Ted Talk, agricultural activity is by far the largest contributor of greenhouse gases. Thus "The Challenge Ahead" is an excellent teaser for any introduction to the field of demography, and it can be used to spur discussion about the importance of the field for tackling some of the most formidable challenges of the twenty-first century. Note that The Sociological Cinema has previously recommended clips that explore problems associated with population (here, here, and here). Submitted By: Lester Andrist  A factory run by robots in Fremont, CA. Tags: capitalism, economic sociology, globalization, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, science/technology, theory, assembly line, deskilling, jobs, labor, reskilling, robotics, 00 to 05 mins Length: 3:58 Year: 2012 Access: New York Times Summary: This NYT video examines innovations in robot technology used for factory production (see associated article). These robots are far more sophisticated than typical factory robots, and they have important implications for work, labor, and the geography of the global economy. As Marx predicted, global competition drives producers to mechanize their operations to drive down costs. For example, as the article notes, "In one example, a robotic manufacturing system initially cost $250,000 and replaced two machine operators, each earning $50,000 a year. Over the 15-year life of the system, the machines yielded $3.5 million in labor and productivity savings." The robots are replacing huge numbers of low and mid-skilled workers, making assembly lines more efficient and creating some higher skilled jobs. At 2:50, a representative from a robotics company states "We don't view robots as a way to eliminate the labor, it's just an opportunity to raise that skill set and help everybody realize a better life as a result of that, get them out of that repetition and into a place where they can earn a higher wage and be more successful." Viewers may reflect on this highly optimistic view. In some cases, these advanced technologies are bringing manufacturing jobs now held in countries like China back into the US. With the automation of much manual labor, the new jobs are often safer - but they also have new forms of stress and higher insecurity. However, many people who lose their jobs do not have access to the education and training needed to reskill themselves for the new jobs. Furthermore, such technologies might lead to the increasing polarization of jobs in terms of both skills and wages. Who wins and who loses when robots replace human labor? Image by Paul Sakuma/Associated Press Submitted By: Paul Dean  Dancers in the De Wallen red-light district, Amsterdam Dancers in the De Wallen red-light district, Amsterdam Tags: capitalism, children/youth, commodification, consumption/consumerism, crime/law/deviance, gender, globalization, sex/sexuality, human trafficking, prostitution, sex trafficking, slavery, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 1:40 Access: YouTube Summary: This short clip is a PSA from Stop The Traffik (STT), an international charity focused on ending human trafficking. The clip was shot in the famous De Wallen red-light district in Amsterdam and features six women dancing in a typical brothel. Their performance captivates, and a crowd of men soon gathers in the street to watch. The performance abruptly ends and an electronic billboard overhead reads, "Every year, thousands of women are promised a dance career in Western Europe. Sadly, they end up here." Many people are aware of the connection between human trafficking and sexual exploitation, and indeed the Netherlands is listed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime as a primary country of destination for victims of human trafficking. The reality is people are trafficked for a number of reasons, not all having to do with sexual slavery. STT defines human trafficking as the act of deceiving or taking people against their will, to be bought, sold and transported into slavery for sexual exploitation, to be used in sweat shops, circuses, in sacrificial worship, forced begging, or to be used as child brides, farm laborers, unwilling human organ donors, and as domestic servants. Human trafficking appears to be growing, and according to STT, 2 to 4 million men, women and children are trafficked across borders and within their own country every year. More than one person is trafficked across borders every minute, which is equivalent to ten jumbo jets every day. The clip does well to capture viewers' attention and might be an effective foray into what must be a much deeper discussion about trafficking. One can approach the issue in terms of globalization by considering the global flows of trafficked humans from less developed countries to more developed countries. To what extent is human trafficking explained by the conditions of the global economy, where a steady supply of children are sold by people in the global south, who face extreme poverty, in order to meet the demands of those in the global north, who have more than enough? This video would work well in tandem with another clip on The Sociological Cinema, which explores the biography of a young woman who was forced into prostitution in the United States. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Tags: demography/population, environment, food/agriculture, globalization, inequality, rural/urban, anthropocene, great acceleration, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 3:29 Access: YouTube Summary: In sparkling electric blue, this narrated visualization illustrates the impact humans have had on the Earth's ecosystems from the time of the industrial revolution to the present. Referring to a new geological epoch, the narrator boldly announces, "Welcome to the anthropocene." The anthropocene is marked by the decisive role humans now play in shaping the state, dynamics and future of the Earth system. Among other indicators, scientists point out that anthropogenic processes now account for more sediment transport than natural processes, such as the erosion from rivers. Humans have also measurably altered the composition of the atmosphere, oceans, and soils, as well as the cycles associated with elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. The more than seven billion of us who currently reside on the planet now breath a chemically altered atmosphere of our own making, and we are witnessing the spread of oceanic dead zones. From a sociological standpoint, the adjective "anthropogenic," which simply denotes something that is produced by humans, is imprecise. It is not the mere presence of billions of homo sapiens which has altered the Earth's systems; rather, it is the way homo sapiens interact with the Earth's systems—our social processes. The clip works well as a way to enter into a discussion about environmental sociology. Specifically, one could easily draw on it to highlight the tension between understanding how changes in the environment get framed as problems by scientists, media, and other social actors, and how certain environmental changes have a real ontological status, irrespective of that framing. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  7 billion: how your world will change Tags: demography/population, globalization, inequality, rural/urban, thomas robert malthus, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2010 Length: 2:58 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip, although made in 2010, examines the world as we hit a global population of 7 billion people (October 2011). Topics explored in the video include the impact of having 7 billion inhabitants living on the globe, the increasing length of the human life span, the unbalanced human consumption of scarce resources, and unequal living conditions. I include this video in my lecture on stratification, specifically in reference to Malthus's view of favoring inequality as a form of population control. It also can be used when covering demographics. The clip was created by National Geographic magazine as part of their 2011 year-long series on world population; additional resources are available on their website. Click here for another clip on The Sociological Cinema that contextualizes issues of global population and inequality. Submitted By: Rachel Sparkman  Tags: capitalism, commodification, corporations, economic sociology, globalization, inequality, marx/marxism, organizations/occupations/work, capital flight, feminization of poverty, maquiladoras, world-systems theory, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006; 2012 Length: 4:04; 2:58 Access: clip 1 on YouTube; clip 2 at the New York Times Summary: These two clips examine the role of low wage work in the global economy. The first clip looks at maquiladoras (multinationally-owned factories operating in tax-free zones in low wage countries) from the documentary Maquilapolis (city of factories). It presents the stories of two female maquiladora workers. Carmen works the graveyard shift at a factory that produces television parts. She was attracted to the maquiladoras because it paid better wages than the rest of Mexico. However, she ultimately suffers from kidney damage and lead poisoning from her years of exposure to toxic chemicals and her employers that do not allow workers to drink water or go to the bathroom during their shift. In a global economy, corporations are attracted to places like Mexico because of their tax-free zones that offer tax breaks and cheap labor that is easily exploitable. Employers expect labor, which is mostly female, to have "agile hands and would be cheap and docile". Ultimately, Carmen's employer moved from Mexico to Indonesia to find cheaper labor and earn higher profits. The clip discusses female labor as a "cheap commodity" that is easily discarded if they become less productive or defend their labor rights. The second clip documents workers at a Chinese Foxconn factory that employs 120,000 workers with low pay and dangerous working conditions. The clips offer a good illustration of world-systems theory, and viewers can be encouraged to think about the role of maquiladoras in the global economy. How does value flow through the global economy? How is work, gender, and inequality linked to maquiladoras and the mobility of transnational corporations around the world? Do maquiladoras reproduce poverty or can they help nations rise in global value chains? Submitted By: Paul Dean |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed