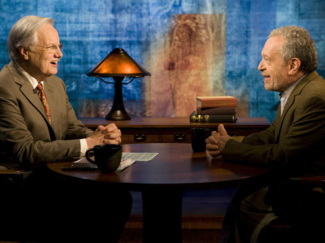

Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Robert Reich discusses economic inequality with Bill Moyers Tags: capitalism, class, consumption/consumerism, corporations, crime/law/deviance, economic sociology, globalization, government/the state, inequality, organizations/occupations/work, political economy, politics/election/voting, science/technology, robert reich, social mobility, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2013 Length: 56:46 Access: Moyers & Company Summary: In this interview on Moyers & Company, former Secretary of Labor and professor of public policy at the University of California in Berkeley, Robert Reich discusses economic inequality and the worrisome connection between money and political power. Reich notes that "Of all developed nations, the US has the most unequal distribution of income," but US society has not always been so unequal. At about the 6:20 mark, the clip features an animated scene from Reich's upcoming documentary, Inequality for All, which illustrates that in 1978 an average male worker could expect to earn $48,302, while an average person in the top 1% earned $393,682. By 2010, however, an average worker was only earning $33,751, while the average person in the top 1% earned $1,101,089. Wealth disparities have also been growing, and here Reich explains that the richest 400 Americans now have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. What happened in the late 1970s to account for the current trend of widening inequality? According to Reich, there are four culprits. First (at about 19:10 min), a powerful corporate lobbying machine has successfully lobbied for laws and policies that have allowed for wealthy people to become even more wealthy, often at the expense of the poor. Examples include changes to antitrust, bankruptcy, and tax legislation. Second (at 34:00 min), Reich argues that unions and popular labor movements have been on the decline, which means employers have been under less pressure to increase wages over time. Third (at 38:30 min), while globalization hasn't reduced the number of jobs in the US, it has meant that employers often have access to cheaper labor, which has had the effect of driving down wages for American workers. He points out that in the 1970s, meat packers were paid $40,599 each year. Now they only earn $24,190. Fourth (at 38:30 min), technological changes, such as automation, have had the effect of keeping wages low. He concludes that there is neither equality of opportunity nor equality of outcome in the U.S., and unless big money can be separated from politics, the U.S. economy is unlikely to free itself from this viscous cycle of widening inequality for all (Note that a much shorter video featuring Reich's basic argument is also located on The Sociological Cinema). Submitted By: Lester Andrist

2 Comments

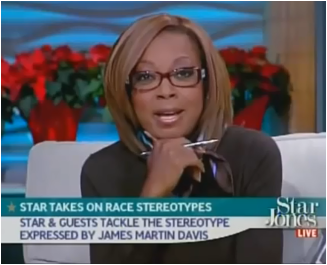

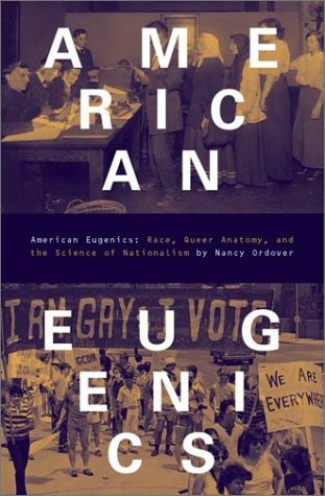

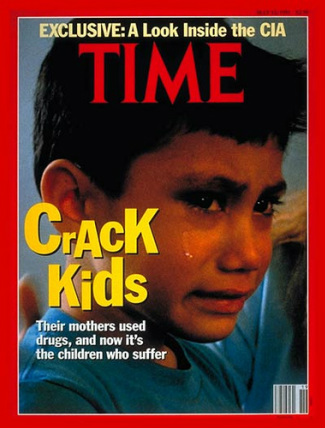

Star Jones analyzes the racism of one of her guests Star Jones analyzes the racism of one of her guests Tags: children/youth, crime/law/deviance, discourse/language, gender, immigration/citizenship, inequality, intersectionality, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, sex/sexuality, stereotypes, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2008 Length: 8:50 Access: YouTube Summary: Star Jones briefly hosted a live talk show from August 2007 until February 2008, and in one of the show's segments she covered the story of Kelsey Peterson, a 25-year-old teacher who sexually assaulted her 13-year-old student, who happened to be an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. The above video features a telephone interview, where Jones asks Peterson's attorney, James Martin Davis, whether he believes it is possible for a 13-year-old child to give consent. Martin responds, "I resent the word 'child.' You're baby-fying this kid. This kid is a Latino machismo teenager...Is there anyone in the world who has a higher sex drive than a teenage boy." Jones admonishes Martin for his casual racism and ends the interview. In a follow-up segment, she invites the attorney for the victim, Amy Peck, and scholar Marc Lamont Hill to discuss the racist exchange, as well as the impact of racial thinking on the case. Although Star Jones and her guests largely frame the interview in terms of race, this video offers a nice foray into a larger discussion about how multiple dimensions of inequality intersect to shape the way people experience the criminal justice system and whether victims of crime become the recipients of public sympathy. Jones suggests a useful thought experiment by asking people to imagine that the race and gender of the participants are reversed. The question can be usefully posed: How would the story be discussed and reported by the media and interested parties if the victim was a young white girl and the perpetrator an older Latino man? Also, what difference does it make that the teenager was an undocumented Mexican immigrant, and how might the current discourse surrounding Mexican immigrants shape sympathy for the victim? Submitted By: Lester Andrist  Decriminalization has helped Portugal with drug abuse. Decriminalization has helped Portugal with drug abuse. Tags: crime/law/deviance, addiction, drugs, drug decriminalization, labeling theory, portugal, prisons, 11 to 20 mins Year: 2011 Length: 14:08 Access: YouTube Summary: In the US, there has been increasing concern over the war on drugs, including its disastrous effects on society and how the issue of drugs might be approached differently. One alternative approach is drug decriminalization, which Portugal recently implemented. In 1999, almost 1% of Portugal's population were heroin addicts, and they had the highest rate of drug-related AIDS deaths in the EU. In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all drugs (i.e., they decriminalized possession but the production and distribution of drugs remained illegal). In this model, drug abuse is treated as a public health issue rather than a criminal issue; their goal is harm reduction for both the individual and society. This video examines social outcomes after 10 years of decriminalization (for related readings, see this New Yorker article and white paper from the Cato Institute): serious drug use declined significantly (especially among youth), the burden on the criminal justice system eased, the number people willingly seeking treatment increased, and drug-related deaths and infectious disease fell. Despite people's fears, Portugal has also NOT become a haven for “drug tourism.” While the system has its critics and difficulties (e.g., enforcing laws prohibiting distribution), support for decriminalization has grown within Portugal with few calling for its repeal. The video also offers an interesting application of labeling theory. Under labeling theory, social control agents are those individuals and institutions which apply symbols/labels (e.g., drug addict) to deviant behavior. Police, social workers, and medical physicians apply such labels to drug users in the video, but meanings assigned through this process of social interaction differ from those applied in the US and other systems of drug control. In this instance, the deviant behavior is viewed as a health problem (rather than a criminal problem), and social control agents promote more conscious and responsible consumption of drugs. The stigma of being labeled a "drug user" has less negative effects on the person being labeled. This illustrates how the label applied does not come from some objective reality, but emerges through a process of social interaction. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Drones will be big business, but raise privacy concerns. Drones will be big business, but raise privacy concerns. Tags: crime/law/deviance, foucault, government/the state, science/technology, theory, war/military, drones, panopticon, surveillance, unmanned aerial vehicles, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 4:41 Access: New York Times Summary: Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, are the "future of aviation." The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which regulates the use of drones and currently limits the commercial use of drones in the US, is likely to loosen this restriction by 2015 and private industry is positioning itself for a commercial boom in drones. And while the US government has mostly used drones for surveillance and combat in the war on terror, the government has weighed the use of drones for surveilling its own citizens. As noted by the NYT, Senator Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said this year: “This fast-emerging technology is cheap and could pose a significant threat to the privacy and civil liberties of millions of Americans. It is another example of a fast-changing policy area on which we need to focus to make sure that modern technology is not used to erode Americans’ right to privacy.” From a Foucauldian perspective, the possibility of widespread drone surveillance could be the new Panopticon. In particular, inexpensive drones (<$1000) allow for continuous video footage, facilitating the proliferation of micro-power as individuals, corporations, and government observe others throughout all of society. Furthermore, it is likely to spread throughout a variety of institutions, enabling the use of drone surveillance in search-and-rescue missions, agricultural surveillance, and countless other personal and commercial applications. While Foucault offered the metaphor of surveillance technologies as swarming throughout society, drones offer a very literal extension of this expanding technology. Submitted By: Paul Dean  Eugenic thinking is woven into the fabric of American society Eugenic thinking is woven into the fabric of American society Tags: biology, bodies, class, crime/law/deviance, demography/population, disability, discourse/language, gender, health/medicine, immigration/citizenship, intersectionality, lgbtq, nationalism, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, science/technology, sex/sexuality, institutionalized discrimination, eugenics, subtitles/CC, 11 to 20 mins, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2012; 2013 Length: 15:05; 17:25 Access: YouTube (clip 1; clip 2) Summary: The eugenics movement has a long history in the United States. A popular misconception is that eugenic thinking and the associated practices were uniformly abandoned after the Third Reich's genocidal intentions were laid bare at the end of the Second World War. In point of fact, eugenic ideologies and practices have been recalcitrant features of American social institutions right up until the present day. In her book American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism, Nancy Ordover remarks on the resiliency of the ideology, "Eugenics..is a scavenger ideology, exploiting and reinforcing anxieties over race, gender, sexuality, and class and bringing them into the service of nationalism, white supremacy, and heterosexism." In earlier decades eugenicists could openly discuss stemming the "overflow" of immigration, as an effort to "dry up...the streams that feed the torrent of defective and degenerate protoplasm." The language of eugenics would eventually change, but the core ideas have remained; socially deviant groups and socially undesirable conditions are seen by eugenicists as biologically determined. The above clips are news stories, which draw attention to two recent manifestations of eugenics policy. The first clip chronicles the experience of an African American woman who was legally sterilized in the late 1960s in North Carolina after giving birth to her first son. The clip reports that between 1929 and 1974 approximately 7,600 North Carolinians were sterilized for a host of dubious reasons, from "feeble-mindedness" to "promiscuity." But while North Carolina's victims included men, women, and children, Ordover's research points out that the victims were overwhelmingly women and African American (by 1964 African Americans composed 65% of all women sterilized in the state). The first clip, then, is an example of how eugenics became institutionalized with the force of law, but the second news clip examines a case of institutionalized eugenics in California, which existed without the explicit consent of law. In 1909 California became the third state to pass a compulsory sterilization law, allowing prisons and other institutions to sterilize "moral degenerates" and "sexual perverts showing hereditary degeneracy." By 1979, when the law was finally repealed, the state had already sterilized as many as 20,000 people, or about one-third of the total number of such victims throughout the United States. One learns from the news clip that between 2006 and 2010, 148 women were sterilized by doctors who continued to be guided by the precepts of their eugenic ideology. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  "Crack babies" became a moral panic in the 1980s "Crack babies" became a moral panic in the 1980s Tags: aging/life course, children/youth, crime/law/deviance, discourse/language, health/medicine, inequality, media, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, crack, cocaine, drugs, moral panic, war on drugs, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2013 Length: 10:10 Access: New York Times Summary: In their book, Policing the Crisis, Stuart Hall and his coauthors investigate what was reported to be a sharp increase in muggings that occurred in Britain at the start of the 1970s. In fact, despite much public concern, a rash of criminality could not be verified, leading the authors to consider a far more likely scenario, that British society was gripped by something called a moral panic. "When the official reaction to a person, groups of persons or series of events is out of all proportion to the actual threat offered, when 'experts', in the form of police chiefs, the judiciary, politicians and editors perceive the threat in all but identical terms, and appear to talk 'with one voice' of rates, diagnoses, prognoses and solutions, when the media representations universally stress 'sudden and dramatic' increases (in numbers involved or events) and 'novelty', above and beyond that which a sober, realistic appraisal could sustain, then we believe it is appropriate to speak of the beginnings of a moral panic." The public fear about widespread muggings in Britain can be likened to the sudden swell of concern in the U.S. regarding the spread of crack cocaine in the 1980s. Unlike muggings, cocaine use was truly on the rise, but in many ways the dilemma was similarly blown "all out of proportion." The above video chronicles the role played by the media in exaggerating the scale of the cocaine problem and the dire health consequences predicted for the children of women who used the drug. As expressed by one politician, there was a belief that crack babies would "overwhelm every social service delivery system that they come into contact with throughout the rest of their lives." As the video explains, many people born to mothers who were addicted to crack have been able to lead lives free of the health complications foretold by newscasters. So if the actual threat posed by the growing use of cocaine was something different than the one portrayed in the media, why did the moral panic about "crack babies" take hold in the public consciousness? One explanation is that the preliminary research, which first raised the issue of potential health consequences for these children, coincided with President Ronald Reagan's War on Drugs. As the legal scholar Michelle Alexander notes, in an effort to secure funding for the new war, Reagan actually hired staff in 1985 to publicize the emergence of crack cocaine, and a national tragedy involving "crack babies" was just the kind of story they sought to promote. A second explanation for why the moral panic took hold ties in the fact that the War on Drugs has been a racist war from the very start, and the idea of a scourge of crack-addicted pregnant mothers aligned well with long held, racist stereotypes of black welfare queens who raise children in crime-infested neighborhoods. Submitted By: Lester Andrist  While Avon is an innovator, Stringer proposes being a conformist. While Avon is an innovator, Stringer proposes being a conformist. Tags: crime/law/deviance, theory, strain theory, the wire, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2002 Length: 4:10; 3:07 Access: YouTube (clip 1; clip 2) Summary: Robert Merton’s strain theory was an early sociological theory of crime. Merton argued that mainstream society holds certain culturally defined goals that are dominant across society (e.g. accumulating wealth in a capitalist society). His strain theory focused on whether an individual rejects or accepts society’s cultural goals (wanting to make money) and the institutional means to attain those goals, resulting in a typology of criminals and non-criminals: 1) Conformists accept the culturally defined goal of success and the institutional means society defines as appropriate to reach that goal (e.g., advancing one’s education); 2) Innovators accept the culturally defined goal of financial success, but cannot or do not follow society’s rules (e.g. lacking money for education, disregarding the law) in their pursuit of wealth; 3) Ritualists do not believe they can attain the culturally defined goal of accumulating wealth, but continue to work through society’s acceptable pathways because they are supposed to; 4) Retreatists reject the goal of wealth and the means society deems acceptable, thereby escaping society often through substance use; and 5) Rebels redefine society’s goals and create new institutional means or work outside the system to pursue them (see this framework visually). These types are well illustrated through characters in The Wire. In this first clip, gang leaders Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell debate how they can reclaim their top “real estate” for selling heroine. Avon states how he is a gangster, or from Merton’s perspective, an innovator. In contrast, Stringer Bell pushes to work with Marlo (another gangster not shown in these scenes) and eventually desist from the drug trafficking scene, making “straight money” as a conformist. In the second clip, Johnny and Bubbles (two drug users in the show) debate how to make money, with Bubbles wanting to get paid helping the police, thus working toward being a conformist. But Johnny ultimately convinces Bubbles to help him innovate through petty crime simply to feed his addiction (i.e., becoming a retreatist). Note: this is an edited version of Dr. Mayeda’s original blog post on The Cranky Sociologists. See our other posts using The Wire to teach rational choice theory, class consciousness, and cultural capital. Submitted By: David Mayeda, PhD  The Onion uses satire to critique racial profiling. The Onion uses satire to critique racial profiling. Tags: crime/law/deviance, inequality, intersectionality, race/ethnicity, racial profiling, stereotypes, white privilege, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2011 Length: 1:53 Access: The Onion Summary: From the War on Drugs, which disproportionately targets African-American communities, to racial profiling by police, race continues to play a powerful role in our criminal justice system. In her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander describes how "the U.S. criminal justice system functions as a contemporary system of racial control" and has disastrous effects on the African-American community. This satirical news clip from The Onion plays on this unfortunate reality. It begins with reporting of a 16-year-old girl who supposedly stabbed a girl to death. At her arraignment, the judge in her case states "due to the extreme and violent nature of this crime, this court finds it fitting to try the defendant as an African-America. Henceforth, you will be referred to for the jury by the name Mendel Brown." The news commentator continues: "Now that Hannah has been ruled black, the court has instructed local media to assume she is guilty and the police have retroactively charged her with assaulting her arresting officer." The clip concludes by the commentator noting that the girls parents argued that, "their daughter should at most be tried as a Black celebrity, or at least a stunningly beautiful Filipino lady." Viewers might consider what makes this satire so funny? What does it say about racial stereotypes? Furthermore, how might we interpret this from an intersectional perspective? For example, would the joke work the same way if commentator reported that she would be tried as a black female or a white male? One could argue that there is something distinct about how black masculinity, as a unique intersection of race and gender, is constructed in our culture. Taken from the opposite point of view, what does this say about white privilege? If Black males are disadvantaged, white privilege may work by giving whites the benefit of the doubt in criminal activity. They need not worry about the immediate perception of guilt. For similar videos, see Dave Chappelle's satirical look at criminal justice system, an experiment on racial profiling in crime, and this analysis of racial profiling with the NYPD's stop-and-frisk policy. Submitted By: Paul Dean  "Come at the king, you best not miss." ~ Omar "Come at the king, you best not miss." ~ Omar Tags: crime/law/deviance, theory, rational choice theory, the wire, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2002 Length: 5:57 Access: YouTube Summary: In The Wire, Omar is a Robin Hood-esque individual who incessantly steals drugs and money from Avon Barksdale’s gang. In these two snippets from season 1, we first see Omar and his crew at night preparing to steal drugs/money (or “the stash”) from one of the Barksdale sites. Then the next day we see Omar and his crew try to carry out their plan. These scenes are an excellent illustration of rational choice theory, which purports that individuals are generally rational, potential criminals, who would engage in crime if they could get away with it. In other words, we have a sense of free will and weigh the pros and cons that go into committing different crimes. Rational choice theory, however, has a robust range of components. Specifically, all of us are potential criminals who 1) consider how crime is purposeful; 2) sometimes have clouded judgement about crime due to our bounded rationality; 3) make varied decisions based on the type of crime being considered; 4) have involvement decisions (initiation, habituation, and desistance) and event decisions (decisions made in the moment of a crime that should reduce the chances of being caught); 5) have separate stages of involvement (background factors, current life circumstance, and situational variables); and 6) may plan a sequence of event decisions (a crime script). Note in particular Omar’s bounded rationality—how his judgement is clouded by his despise for the “Barksdale Crew,” as Omar’s crew asks at night in the car why they need to keep hitting up the Barksdale stash houses, even though more vulnerable targets exist. Also take note of the crime script that is supposed to work out well, but doesn’t, since Omar and company are not aware of the amount of firepower present in the stash house being targeted. Note: this is an edited version of Dr. Mayeda's original post at The Cranky Sociologists. Submitted By: David Mayeda, PhD  The Joker terrorizes his victims with a prisoner's dilemma The Joker terrorizes his victims with a prisoner's dilemma Tags: crime/law/deviance, methodology/statistics, theory, fiction, game theory, mathematical sociology, prisoner's dilemma, rational choice theory, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012; 2008 Length: 2:59; 4:52 Access: clip 1; clip 2 Summary: In sociology, game theory is often deployed by those working from a rational choice theoretical perspective. As such, it is primarily concerned with the rational and strategic interactions between agents and has been applied to analyzing a broad range of situations, from criminal confessions to the stockpiling of nuclear arms. One insight upon which the theory is based is that while a given course of action may appear to be most rational or beneficial from the perspective of a single actor, the action may be less beneficial when considering the possible actions taken by other actors. The first clip examines the prisoner's dilemma as the paradigmatic example of game theory. Police bring two suspects, Xavier and Yoshi, to the police station and place each in a different room. The police then present each suspect with their dilemma: a) If one confesses and turns on the other, the confessor will go free and the other will get 10 years in prison; b) if they both confess, each gets 8 years in prison; and c) if neither confess, they will each spend only a month in prison on a lesser charge. The suspects have a choice between cooperation and defection, and as the clip explains, given that neither suspect is able to coordinate with the other, each will likely turn on the other as the most rational course of action. A second illustration (i.e., clip 2) of this type of dilemma, or "game," comes from the 2008 film The Dark Knight. In this clip Batman's nemesis, the Joker, attaches explosives to two ferries. On each ferry is the detonator capable of blowing up the other ferry, and the occupants of each ferry are told the only way they can assure their survival is to be the first to press the detonator. One may deem this comic book scenario to be too far fetched, and the situation presented to the prisoners may be dismissed as an inaccurate model of law enforcement practices; however, I think game theory continues to enjoy surges in popularity precisely because it is readily applicable to such a broad range of social situations. In his 2004 novel, Forty Signs of Rain, Kim Stanley Robinson creates a character who endures a frustrating commute to work in Washington D.C. and applies game theory to make sense of his misery, "In traffic, at work, in relationships of every kind—social life was nothing but a series of prisoners' dilemmas. Compete or cooperate? Be selfish or generous?....By and large Beltway drivers were defectors." Submitted By: Lester Andrist |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed