Mannequins are rebuilt in this Pro Infirmis video on disability Mannequins are rebuilt in this Pro Infirmis video on disability Tags: art/music, bodies, consumption/consumerism, culture, disability, discourse/language, inequality, knowledge, disability porn, stereotypes, subtitles/CC, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2013 Length: 4:29 Access: YouTube Summary: In this four minute video from the Swiss company Pro Infirmis, five people with visible disabilities arrive at an artist's studio. After introductions, the artist begins measuring the dimensions of each person's body. His team then begins sawing into a collection of store mannequins, and once dismembered, the mannequins are reconstructed so they more closely resemble the body designs of the artist's new models. After some polish, the new mannequins are unveiled and eventually displayed in stores along one of Zurich's main streets, just in time for the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. The project's title is a rhetorical question and a command, "Because Who Is Perfect? Get Closer." Indeed, no one is perfectly able-bodied. Whether visible or invisible, on some level it is true that all bodies can be said to have "malfunctions," but the deeper reason no one is perfect is because the idea of what constitutes perfection is itself elusive. Yet, most people go about their daily lives seduced by the illusion that distinguishing "able-bodied" people from "disabled" people is as straightforward as distinguishing apples from oranges. For instance, there is a Thor fandom that celebrates Chris Hemsworth's shirtless body as the epitome of perfection. Mall shoppers too routinely evaluate clothing for themselves and others by first seeing it draped over what is supposed to be a mold of a perfect body. Capitalist institutions, from the Hollywood film industry to clothing retailers, routinely place the able-bodied ideal on a pedestal, implicitly exalting a particular type of body as the standard by which all bodies must be evaluated, and it is on this point that the Pro Infirmis video is both refreshing and subversive, for it takes what are assumed to be imperfect bodies and places them in a space typically reserved for perfect bodies. These new mannequins of unfamiliar proportions stop passersby in their tracks and encourage them to reconsider the types of bodies that belong in storefronts, but while the video captures a useful disruption in the usual discourse on bodies, in my view it fails to truly provoke onlookers to reassess their casual assumptions about bodies as either working or broken, and as either worthy or unworthy of representation. No, the video leaves this binary cultural logic unscathed. For instance, one finds in the video that "able-bodied" mannequins are the clean slate from which "disabled" mannequins are born. There is a manufacturing montage that puts to rest any radical doubts as to whether these two species of mannequin have anything in common. Finally, when displayed in the Zurich storefronts, the altered mannequins remain almost hermetically sealed from the original mannequins, which have been scuttled away for the event. To truly "get closer," as the video commands us to do, I think it is important to collapse this casual, Manichean distinction between the able-bodied and the disabled. A truly radical video might instead show the old mannequins displayed alongside the new ones, and the displays would be left in place long after the International Day of Persons with Disabilities was over. Submitted By: Lester Andrist

2 Comments

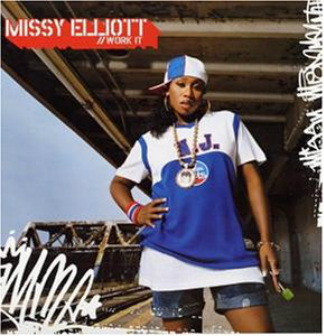

Meryl Streep shows how culture shapes perceptions of choice Meryl Streep shows how culture shapes perceptions of choice Tags: art/music, culture, cultural influence, cultural trends, fashion, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2006 Length: 1:46 Access: YouTube Summary: In this short clip from the film The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Meryl Streep plays Miranda Priestly, the editor-in-chief of a top fashion magazine. Anne Hathaway plays Andy Sachs, an aspiring journalist, who has recently started as a junior personal assistant to Miranda. While it’s a job many would kill for, Andy sees it as a stepping-stone and understands fashion as a largely superficial institution—one completely disconnected from her life and how she understands herself. I often use cultural trends surrounding baby names to explain to students how their names are a reflection of cultural trends. It’s a great way to introduce sociological thinking to students. This clip could be shown alongside such a discussion to help students think about what they wear in similar ways, getting them to think about the cultural influences at play in helping them make decisions about what to wear (and perhaps just as important, what not to wear). Miranda’s great critique of Andy’s subtle scoff in this scene is of Andy’s belief she is somehow “outside” of fashion—a belief Miranda finds laughably naïve. While we might think of clothing (as we do with the selection of baby names) as an intensely personal decision, Miranda helps to frame everyone’s fashion choices—even those who might not feel they are making “choices”—as, at least in part, guided by the cultures in which we live and the institutions that produced the clothing available. The clip could also foster a class discussion about globalization by thinking about production and dissemination processes within the fashion industry. Submitted By: Tristan Bridges  "Is This Art?" (fig 2: If This Is Art); ©Maciej Ratajski (artist) "Is This Art?" (fig 2: If This Is Art); ©Maciej Ratajski (artist) Tags: art/music, organizations/occupations/work, social construction, theory, art worlds, howard becker, networks, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2010 Length: 2:22 Access: YouTube Summary: This humorous video was recorded by Ken Tanaka during his visit to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (Tanaka is an alter-ego of comedian and actor, David Ury). In this clip, Tanaka expresses his appreciation for what he believes is an installation piece called "Please Do Not Enter." The gallery guard is quick to correct Tanaka, informing him that, "This is not artwork" but rather the remnants of an exhibit that closed two days ago. But Tanaka presses on, articulating the ways in which this particular combination and composition of materials (a trash can, cardboard, and Styrofoam) speak to him: "I thought this was a good commentary on the disposable American society," he says. Eventually, a crowd starts to gather around the exhibit, and the gallery guard laughs saying, "You got everybody thinking it's art." To which Tanaka responds, "But it is art. Otherwise it wouldn't be in a museum." This clip can be used to illustrate Howard Becker's theory of art worlds. In his book by the same name, Becker (1982) argues that art worlds refer to "the network of people whose cooperative activity, organized via their joint knowledge of conventional means of doing things, produces the kind of art works that art world is noted for" (x). In short, this social organizational (rather than aesthetic) approach to art suggests that a network of people produce art and determine what art is. In this clip, Tanaka's artistic assessment of "Please Do Not Enter" is challenged, as the gallery guard is privy to the fact that the larger art world would not consider it art. Tanaka, of course, also draws upon an art world approach in his defense for why it must be art, "Otherwise it wouldn't be in a museum." Museums represent a segment of the network of people that make up an art world, and they lend institutional legitimacy to whether something is categorized as art or not. Notably, this video was shot in the American folk art wing of the museum. Created by artists without formal training, American folk art was overlooked by the larger art world for a long time. Once folk art began to receive attention from mainstream players in the art world, such as collectors, galleries, and eventually museums, the genre came to be defined as a valuable artistic expression, with some pieces now selling for over a $1 million. This video would also pair well with Ashley Mears' (2011) ethnographic study Pricing Beauty, in which she applies Becker's theory to the world of modeling, illustrating how a network of people come to determine what defines a good "look." Submitted By: Valerie Chepp  The NiqaBitch video protests France's burqa ban The NiqaBitch video protests France's burqa ban Tags: art/music, bodies, crime/law/deviance, gender, immigration/citizenship, inequality, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, religion, sex/sexuality, burqa, burqa ban, chandra talpade mohanty, femininity, feminism, male gaze, niqa, postcolonialism, racism, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2010 Length: 2:17 Access: YouTube Summary: This clip features a protest against France's recent Burqa ban, which went into force in 2011. The new law stipulates that anyone caught wearing the niqab or burqa in public could face a fine of €150, or be forced to take lessons in French citizenship. The performance of the two women in the video challenges the resistance/subordination binary, which typically frames discussions about what it means when non-Western women don the veil. By sexualizing their veiled bodies, the women challenge ideas about whether wearing a veil is necessarily an expression of women's oppression, just as it challenges whether wearing hot pants and high heels is necessarily an expression of women's ability to resist oppression (Note that the ban went into force after the video was made). Moreover, by performing a sexualized femininity they are apparently able to navigate the streets of Paris without being disciplined, and their short walk raises a number of provocative questions. First, to what extent are the two women able to “break” the law because they have garnered the approval of the heterosexual male gaze? How might people react to these women if they did not fit the archetype of attractive females? This clip provides an excellent window into Chandra Mohanty's acclaimed paper “Under Western Eyes.” Mohanty takes issue with the way that Western feminists assume that wearing the veil is a symbol of oppression and fail to give a voice to the women who wear these clothes. It is unfair for Westerners to assume that the way they themselves dress is a symbol of empowerment without unpacking the systems of patriarchy that inform Western modes of dress. Viewers can also consider whether Westerners have the authority to make judgments about the way non-Westerners dress. Does the government have the right to create laws that ban certain styles of dress? If so, why aren't the religious symbol laws enforced for nuns who wear veils? Submitted By: Pat Louie  Narco Cinema both reflects and shapes Mexican society today. Narco Cinema both reflects and shapes Mexican society today. Tags: art/music, culture, inequality, cinema, drugs, mexico, war on drugs, subtitles/CC, 21 to 60 mins Year: 2011 Length: 23:17 Access: YouTube Summary: Film has always been a reflection of our society, and this exploration of Mexican cinema is a reflection of drugs, culture, and inequality in contemporary Mexico. First, it is an interesting look at how art imitates life and life imitates art. Given the huge role of drug trafficking in Mexico today, the video documents the large film industry built around dramatizing these conflicts. Some of the actors and directors discuss working with drug traffickers in producing some of the films, and the danger of not discussing their relationship in order to stay alive. At the 12:40 mark, the video examines how the music, or corridos, act as a living testimony of narco lore, which in turn, continues the legend that gives birth to more Narco Cinema. Furthermore, this genre of film in Mexico has influenced clothing, home, and car purchases. Although the same could be said for U.S. films (and how they act as catalyst for sub-cultures), in Mexico, these films have given birth to the ideals of building and living a lifestyle to reflect that of narco culture. Second, a more subtle message in the video is about the relationship between drug culture and inequality. The films are very popular among low-income and rural Mexicans for both economic and cultural reasons. Narco cinema are relatively cheaply made "B-movies" (often written, produced, and completed in less than a month) that go straight to DVD and are much more affordable for everyday Mexicans. Therefore, they have a wider audience than the more expensive feature films (only 18% of Mexicans can afford to see movies in a theater). The films also appeal to impoverished Mexicans (especially males) or those struggling to get by in the US. Drug traffickers are often portrayed as "Robin Hood" type characters who help out their hometowns and families. The drug traffickers themselves are usually people that come from rural poverty, and those who become successful in the drug business are often celebrated within the films (the video also notes the rumors that some of the films are financed by drug cartels). But as the narrator notes, while drugs and drug culture are often glamorized, the reality of drug trafficking is the uncontrollable levels of violence and death that come as a result of the drug wars. For example, Mexico experienced 5,630 Narco-related "execution murders" in 2008. American viewers might also consider the role of the US and US-Mexico relations in this process. The film ends with the narrator adding "as long as there is a huge demand for drugs in America, there's going to be blood, drugs, and these kinds of movies flowing out of Mexico." Finally, while gender is never discussed in the video, sociologists have much to think about in terms of the role of gender in both Narco Cinema and the production of this video. Submitted By: JD Villanueva  Youth poets critique the "Oppression Olympics" Tags: art/music, intersectionality, lgbtq, prejudice/discrimination, race/ethnicity, sex/sexuality, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2012 Length: 4:12 Access: YouTube Summary: This poem, performed by two young women in the youth poetry competition Brave New Voices, is an excellent way to introduce students to the concepts of intersectionality and Oppression Olympics. "Oppression Olympics is a term used when two or more groups compete to prove themselves more oppressed than each other." Intersectionality is the theory of thought that draws attention to the ways in which inequalities are intersecting and interlocking, and thus proves the difficulties associated with comparing one group's experience with oppression to another's. The poem specifically chronicles what happens when members of the African American community and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community engage in comparisons of who has had it worse. While the practice of comparing the harms of racism to homophobia isn't new, as sociologist Eric Anthony Grollman points out in this blog post, "the supposed black-versus-gay divide is old, and frankly a little tired." Indeed, as Grollman and the youth poets show, the experiences and activist histories of these two marginalized groups have much in common. Such insight supports what the bisexual Caribbean-American activist poet June Jordan wrote in her book, Some of Us Did Not Die: "Freedom is indivisible, and either we are working for freedom or you are working for the sake of your self-interests and I am working for mine." In addition to pairing this video with Jordan's work, the clip would work well with scholarship by other intersectional thinkers such as Audre Lorde, Allan Johnson, and Patricia Hill Collins. Submitted By: Kendra Barber  Missy Elliott's "Work It" celebrates black women’s sexuality. Tags: art/music, bodies, gender, intersectionality, race/ethnicity, sex/sexuality, feminism, rap music, 00 to 05 mins Year: 2007 Length: 4:25 Access: YouTube Summary: In this music video, rap artist Missy Elliott fills the void in the discussion of pro-sex black feminism. Historically, black voices have been excluded from the sex-positive feminist revolution. In part, the marginalization of black voices is a product of a colonial past that has stereotyped the black body as always already hypersexual (see Saarjite Baartman). As a result, black academics have taken up a “politics of silence” to resist these stereotypes. A potential site to begin the discussion of a pro-sex black feminist discourse is rap music (Skeggs 1993). The female rappers “talk back, talk black” (hooks 1989) to the colonialist system that attempts to contain the expression of women’s sexuality. In Missy Elliott’s hit song “Work It” (lyrics here), she expresses her own kind of sexuality, effectively creating a dialogue for us to rethink our analyses of black women’s sexuality. How does Missy (re)claim her body as a site of desire and empowerment? How does Missy establish herself as an active sexual subject in the song? Does this challenge patriarchal notions of female sexuality? How does she subvert traditional understandings of the black body? Does Missy challenge conventional (white) beauty standards (i.e. celebration of hips, large butt etc)? How, if at all, does Missy’s music differ from other female artists and, specifically, other popular women rappers? Does Missy create a language for other black women to start understanding and theorizing about their sexual experiences? Can we understand the black female body as separate from representations of Saartje Baartman? How does this enhance our understanding of active black female desire? Do you think that rap music is a legitimate medium to begin theorizing about black sexual scripts? Submitted By: Pat Louie  Rapper Macklemore surrounded by Nike products and symbols Rapper Macklemore surrounded by Nike products and symbols

Tags: art/music, capitalism, commodification, consumption/consumerism, marketing/brands, marx/marxism, theory, baudrillard, commodity fetishism, exchange-value, labor, lacan, surplus value, signified, signifier, symbols, use-value, 00 to 05 mins

Year: 2011 Length: 5:33 Access: YouTube Summary: Seattle rapper Macklemore's music video for his thought-provoking song “Wings” is an excellent way to introduce students to Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism. Commodity fetishism is the process of ascribing magic “phantom-like” qualities to an object, whereby the human labour required to make that object is lost once the object is associated with a monetary value for exchange. Under capitalism, once the object emerges as a commodity that has been assigned a monetary value for equivalent universal exchange, it is fetishized, meaning that consumers come to believe that the object has intrinsic value in and of itself. The object’s value appears to come from the commodity, rather than the human labor that produced it. In “Wings,” Macklemore associates this process of commodity fetishism with Nike Air Max athletic shoes, explaining his belief as a child that the shoes would make him into a superstar athlete like Michael Jordan. The value of Nike shoes is displaced from the labour time that went into creating them, and instead is infused with an intrinsic value that comes into being through celebrity endorsement or symbols such as the iconic Nike “Swoosh.” “Wings” becomes a statement on how market capitalism seduces us into purchasing products that promise to make our lives better. Macklemore comes to this realization through the song’s narrative, exclaiming, “Nike tricked us all,” before finally realizing as the song comes to an end that “it’s just another pair of shoes.” Through tracks like “Wings,” Macklemore explores the darker side of consumption, urging listeners to critically rethink the messages imposed on us in capitalist societies that make us feel the need to constantly consume. This video can also be used to teach and distinguish among Marx's notions of use-value and exchange-value, as well as his concept of surplus-value, which is the surplus or profit earned by the capitalist, above and beyond the use-value (labour power) required to produce the object. Viewers may be urged to identify the use-, exchange-, and surplus-values of the Nike shoe in the video. How is value made? Why do we pay $180 for a pair of Nike shoes, but only $20 for a pair of Sketcher shoes? In addition, this video bolsters discussion about the power of symbols and signification (and Baudrillard’s notion of sign-value) in creating cultural meaning embodied in a commodity sign (e.g., the Swoosh on the Nike shoe, or the Apple symbol on an iPhone). Instructors can ask students to name other symbols in popular culture and what they mean to them. Drawing upon Jacques Lacan’s idea of the signifier and signified, instructors can expand the discussion of symbols by asking students to discuss the role of brand symbols in their life. Have they become a part of their identity? Their culture? Their daily lives? In the end, Macklemore speaks to this point: his Nikes are “so much more than just a pair of shoes.” They are “what I am… the source of my youth… the dream that they sold to you.” For another post on The Sociological Cinema that uses Macklemore's music videos to teach sociological concepts, click here. Submitted By: Patricia Louie  Scene from the music video "Same Love" Tags: art/music, inequality, lgbtq, marriage/family, prejudice/discrimination, sex/sexuality, hip-hop culture, homophobia, marriage equality, privilege, 06 to 10 mins Year: 2012 Length: 7:03 Access: YouTube Summary: Seattle rapper Macklemore’s hit track “Same Love” provides a social commentary for the relatively absent discussion of homosexual love in mainstream hip-hop culture. In “Same Love,” Macklemore expresses his support for gay marriage and creates a space for listeners to reflect upon their views of both gay marriage and homophobia—online, in rap music, and in our daily lives. The video tells a story of struggle with sexual identity, acceptance, love, and marriage. The video follows a man from childhood to old age, unraveling a story about the difficulties of navigating queer sexuality in a heteronormative environment. In the song’s opening lines, Macklemore unpacks stereotypical assumptions that society holds of prescriptions that define “gayness,” explaining his own confusion with his sexual identity as a child because he was “good at drawing” and “keeps his room straight.” Macklemore’s music provides a counter-narrative to typical messages in hip-hop centered around sex, money, drugs, and objectifying women. Instead, he uses his music as a forum to spread awareness about social issues. He effectively flips the discourse from the glorification of homophobic language in mainstream hip-hop to a discussion about prejudice and discrimination. Some questions that instructors can ask students include: “What do heterosexual people take for granted at school dances? At parties? At family dinners with their partner? How do these events illustrate some of the privileges associated with being heterosexual? What are some of the ways we “properly” perform heterosexuality in high school? Do you think hip-hop is an effective medium to educate and create discussions about social issues? For another post that features hip-hop music as a forum to engage social issues, click here. Submitted By: Pat Louie  A scene from Victor Kossakovsky's film, "Lullaby." Tags: art/music, class, inequality, theory, bourdieu, homelessness, poverty, social distance, 00 to 05 mins Length: 3:02 Year: 2012 Access: New York Times Summary: Part of the larger multi-media project Why Poverty?, this short documentary film poem entitled "Lullaby" can be used to teach Pierre Bourdieu's concept of social distance. The film depicts homeless people sleeping by A.T.M. machines in banks, and the reactions of people who encounter them. In a description of the film, filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky references the term social distance: "I wanted the film to be more universal—to emphasize the social distance between most people and the homeless people they encounter, wherever they are in the world." While Kossakovsky does not mention Bourdieu, instructors can use the clip and Kossakovsky's quote to initiate a discussion around Bourdieu's application of the term. As Erica Haimes (2003) summarizes in her article, Embodied Spaces, Social Places and Bourdieu: Locating and Dislocating the Child in Family Relationships: "Notions of space and place are central to Bourdieu’s work. He uses the term space literally (activities occur, and actors act, in physical spaces which have practical and symbolic significance in relation to each other) and metaphorically (preferring the term ‘social space’ to ‘society’ (2000:130-5). Actors occupy multiple places within multiple 'relatively autonomous’ fields that together constitute the social space. These places constitute their status, class, social position: their place within society" (11). Bourdieu is interested in understanding the processes that result in people's varying social positions relative to one another or, the social distance between people. After screening the film, instructors can ask: What activities are occurring in this space? How are actors acting? What practical and symbolic significances do these activities and actions have in relation to each other? Further, how do these activities and actions constitute and reinforce the status, class, and social positions of the people in the film? For example, viewers might consider the different activities occurring in this space (e.g., sleeping vs. completing a bank transaction) and the different ways actors act in this space (e.g., laying on the ground, stepping over a sleeping person, turning back around, etc...), and how these different activities and actions shed light on the multiple statuses, classes, and positions—or social distance—actors occupy relative to one another in the film. Does the film succeed at illustrating, in Kossakovsky's words, "the social distance between most people and the homeless people they encounter"? Submitted By: Valerie Chepp |

Tags

All

.

Got any videos?

Are you finding useful videos for your classes? Do you have good videos you use in your own classes? Please consider submitting your videos here and helping us build our database!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed